Recently I am becoming very interested once again in the situation of Romani people in New Zealand. Despite uniformed claims that there are no real Romani ‘Gypsies’ in NZ there is believed to be between 1,200 and 3000 with the most popular sub-group being Romanichal emigrants from the UK and more recently European Roma refugees.

In the 2018 census, 132 people responded by identifying as Romany in the ethnicity category.

Anyone of Romani descent, or with an interest in Romani culture in NZ is welcome to join the FB group: Aotea Romani

Please see the comment section of this blog to see posts from people looking for their kin. I do not moderate the comment section and it has taken a life of its own but maybe it will be of use to you.

**UPDATE**

Thank you to everyone who has commented on this post, your family stories are fascinating and I apologise that I am unable to help you further, I hope you are able to find the answers you are looking for.

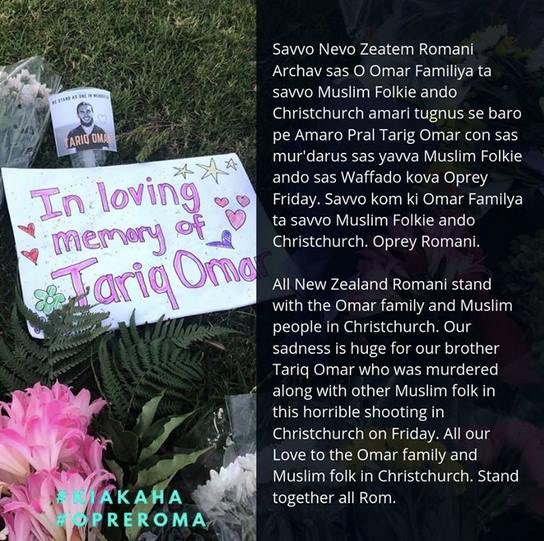

In light of the white supremacist terror attack in Christchurch I would like to take a moment to reflect on all of those who have had their lives cut short by intolerance. Tariq Omar was a Muslim and a Romani. The Romani Community stands together with you at this difficult time and always.

**ORIGINAL 2013 TEXT**

In the UK everyone *feels* like they know what a Gypsy is, it’s also not that uncommon for people to be able to tell the difference between an Irish Traveller and a Romany Gypsy even in-spite of MBFGW’s efforts to cause confusion. But from what I can tell from Google the term Gypsy and Gypsy Travellers in NZ has become incorrectly re-appropriated to mean ‘any old hippy in a truck’. The lifestyle of these housetruckers is indeed interesting, as someone who has spent a great deal of time with New Age Travellers I am perfectly comfortable around them but they’re not ‘quite right’, I am painfully aware that they’re not kin. they are not and never will be Romani. It’s strange really, I read a lot of commentary from American bloggers who discuss the appropriation of the term gypsy to mean ‘free spirited hipster girl’ but as someone who lives in a country with a visible population it is sometimes difficult to truly appreciate the feeling of being erased.

As part of my research I came across an annual ‘Original Gypsy Fair’ (NOT a Gypsy Fair – See UPDATE below) in Invercargill.

The ‘Original Gypsy Fair’ is NOT associated with any Romani Gypsy or Irish Traveller groups. There is active efforts by members of the NZ Romani Community encouraging the fair to change the name. The activist Robert Lovell claims the name is misleading and that copywrite images of Romani people, including of Lovell’s relatives, are being used as promotional material. Not only is this unethical but Lovell is concerned that the misappropriation of the title ‘Gypsy’ leads to confusion and misunderstand, eroding ‘Gypsy’ as an unique ethnic group and any crime committed or incident will be falsely associated with Romani Gypsies

See more from Lovell here and in the comments below.

Remarkably I have discovered a number of articles by New Zealand academics using Māori experiences as a parallel to the Roma experience, I have no expertise to comment on this, nor would I be comfortable doing so as a non-Māori. However if you are interested:

Are Gypsy Roma Traveller communities indigenous and would identification as such better address their public health needs? Link

Below is an account published on two young Roma who attended a leadership study session:

Young Roma Gain New Perspective Far From Home, in New Zealand with the Māori

Published by World Bank Original link

Roma in Central and Eastern Europe are in a unique situation compared to other ethnic groups—they are not indigenous to the continent, nor do they have a homeland like national minorities. However, the socioeconomic disadvantages and discrimination that they frequently face parallel those of other populations throughout the globe, whether they are indigenous peoples, refugees, migrants, or other groups.

Two young Roma leaders, Erika Adamaova from Slovakia and Florin Nasture from Romania, had the unique opportunity in April and May to travel halfway around the world to New Zealand to participate in a youth leadership Study Session on “Democracy in the Pacific.” The program introduced them to some of the parallels and contrasts between Roma and New Zealand’s indigenous Māori population and sparked ideas for new approaches to Roma development programs.

The program was organized by the Pacific Centre for Participatory Democracy—a youth-led NGO based in Gisborne, on the east side of New Zealand’s North Island—and was funded by the New Zealand government, including the Ministry of Māori Development and NZAID. The World Bank Institute also provided support.

The session involved 28 young leaders from New Zealand, Australia, the Pacific Islands, and Indonesia. The organizers were interested in involving Roma to include a diverse set of perspectives. The program aimed to support an inter-cultural and inter-generational dialogue and to identify strategies for sustainable and innovative community development initiatives. During their visit, Erika and Florin also had the opportunity to visit schools, government agencies, and Māori organizations.

Who are the Māori?

Roma and Māori are vastly different ethnic groups, each with their own unique and rich histories and cultures. Māori are an indigenous minority of approximately 620,000 based largely in New Zealand, with small diaspora populations in Australia and other countries. Roma are an ethnic minority spread across the world, but concentrated in Europe, where an estimated 9 to 12 million live. Although Roma originally migrated into Europe from India, they do not have territorial claims there.

There are also similarities. Both Roma and Māori societies are historically based on oral traditions, which made codifying language and creating a written historical record particularly important. Both groups are striking in their internal diversity.

A More Traditional International Conference

The study session incorporated and exposed the participants to Māori culture and traditions. It was held on a marae, the traditional Māori meeting house, which is central to every aspect of Māori life, including weddings and funerals, and serves as the center of the community. Participants were welcomed through Māori ceremony, including the Māori language and music.

“Being on the marae, I finally understood why workshops, conferences and study sessions organized for Roma activists do not achieve their intended impact and effect,” said Erika. “Organizing such events in a four-star hotel is comfortable and pleasant, but to stay in direct interaction with the community and culture motivates and helps the participants to better understand the way of living, thinking and cultural values…The whole Study Session was held in the spirit of Māori culture and traditions.”

Learning from Each Other

Roma attendees compared and contrasted their status in Central and Eastern Europe with that of Māori in New Zealand. The Treaty of Waitangi sets the framework for relations between Māori and the Government, and has influenced the status of Māori in New Zealand. The Treaty was signed in 1840 between representatives of the British government and chiefs of iwi (Māori tribal groups) from across New Zealand. While there is ongoing debate about the meaning of the Treaty, it has been an important basis for recognizing the rights of Māori in New Zealand. In recent years, the Waitangi Tribunal has been hearing claims by Māori against the Crown of breaches of the Treaty. The Government has signed settlements with about 12 iwi.

Increased use of the Māori language has been part of a Māori cultural renaissance in New Zealand. Māori is an official language alongside English. A Māori Language Strategy supports the incorporation of the language across society, including within public services, media, and the arts. Keeping alive the Māori language is seen as critical in sustaining a strong and proud cultural identity. The Roma participants were impressed by the emphasis on language use. Florin noted, “The way to preserve culture is by introducing the Roma language into the schools were Roma children are studying.”

Roma and Māori women face similar challenges. “Talking to Māori women, I realized that the privileged status of men over women is not a part of Māori culture,” said Erika. “An effective approach to promote educational attainment among young Roma mothers would be to implement policies that will encourage young Roma mothers to stay in school.”

Contributing to the lack of education among Roma in Central and Eastern Europe is the unofficial policy in many countries of enrolling Roma children into special schools intended for the mentally and physically disabled. Many of these children eventually drop out, as they have no prospect of attending secondary school or university.

New Zealand, however, has effectively banned special schools, something that some CEE governments still resist. However, many Māori parents—and a small but growing number of non-Māori parents—choose to send their children to bilingual or immersion schools that expose students to Māori language and culture.

A Renewed Sense of Identity

The Roma participants returned home having learned important lessons about fostering cultural identity, improving living standards, and increasing social inclusion. “Many Roma feel there is a gap between the community as a whole and its leaders and elites,” pointed out Florin. “Community participation is key to closing this gap, and it will in turn strengthen Roma identity and a feeling of belonging.”

Florin also emphasized that the whole approach to Roma integration should be turned on its head. “In our region, we take a negative perspective, focusing on the disparity between the Roma and the majority, and creating the appearance of a helpless Roma population.” Māori, on the other hand, are more positive. “They build on existing successes to channel their potential. Like them, Roma should not be people with problems who create problems; we should have the power to overcome our obstacles